http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ygQoxFMVp_E

You might have seen our Facebook posts Friday about watching the Purple Martins roost in Stafford. We posted enough pictures and videos there that I don’t necessarily feel like I need to double post them here. As far as I know, the only readers of this blog are friends with us over there on Facebook (?). The posted YouTube video, though, is from that same night, taken from someone behind us. Jason and his parents are over to the left of the view, I think I was sitting down at this time. I really enjoyed the hour or so we spent out there.

At first, the birds gathered slowly, and seemingly with little purpose. They weren’t flying as much as they were gracefully gliding with the night breeze. I found their movements to be smooth and silky feeling, and it was relaxing to watch. Birds would glide in and out, and the group gathered in numbers and then eventually in momentum and energy. It went from a few groups of hundreds of birds to a more solid group of thousands, coming closer to the ground and moving faster and faster, tweeting, beating wings in unison. They would light on top of the trees and then suddenly move off en masse, and then more birds would join and they would repeat the process, over and over until they finally settled.

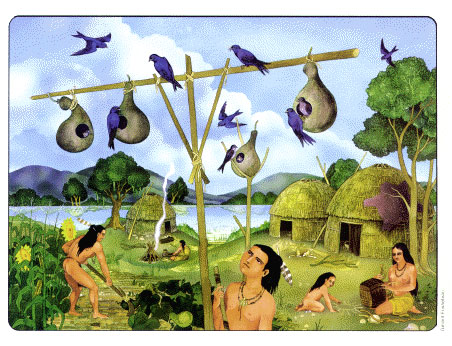

I wanted to share a thought about those graceful little birds that really intrigued me, though. Twelve thousand years ago, before man crossed over the Bering Straight into North America, the martins kept their nests in abandoned chambers of woodpecker nests or hollowed trees. However, at today’s evolutionary point, these birds have stopped nesting naturally east of the Rockies, and are completely dependent on humans setting up houses or gourd-like nests for them. This is a behavior shift that happened over hundreds or thousands of bird generations, as the humans and the martins began mingling.

Back before the urbanization of America, the Native Americans had realized the appeal of these little birds. The purple martins acted like little “scarecrows”, scaring crows away from crops and vultures away from their meat and hides. The Native Americans hung dried out gourds up to attract the birds to nest near them. The birds were potentially able to lay more eggs and successfully raise more offspring to maturity as a result. Over time, the birds returned to these nests year after year, until they “forgot” how to make it on their own in North America. Approximately one million Purple Martin houses are put out by human beings to keep this species of bird going.

By the early twentieth century, this behavior shift was complete. Also, around the 1800s, the introduction of the House Sparrow and European Starling to North America meant that the Purple Martins had competition for resources. The starlings and sparrows take over the houses of the martins, and the martin numbers began declining in the 1980s. Pesticide use and deforestation in the martin’s winter grounds in Brazil have also added to the decline of this species. The Purple Martin Conservation Association formed in 1987, and has been trying to keep these birds from further decline. You can get more information here if you are curious about this association.

By the early twentieth century, this behavior shift was complete. Also, around the 1800s, the introduction of the House Sparrow and European Starling to North America meant that the Purple Martins had competition for resources. The starlings and sparrows take over the houses of the martins, and the martin numbers began declining in the 1980s. Pesticide use and deforestation in the martin’s winter grounds in Brazil have also added to the decline of this species. The Purple Martin Conservation Association formed in 1987, and has been trying to keep these birds from further decline. You can get more information here if you are curious about this association.

This has made me curious about the co-evolution of humans and other species, and also about the ways people help nature. I am not sure if the relationship the martins developed with the humans was negative or positive – while they do benefit from the support of the houses, if we didn’t enable them with the houses in the first place, they might have retained their ability to find their own nests and be sustainable as a species without us. I am going to look for more examples like this to illuminate in future posts.