-

Nevada’s Wild Horses

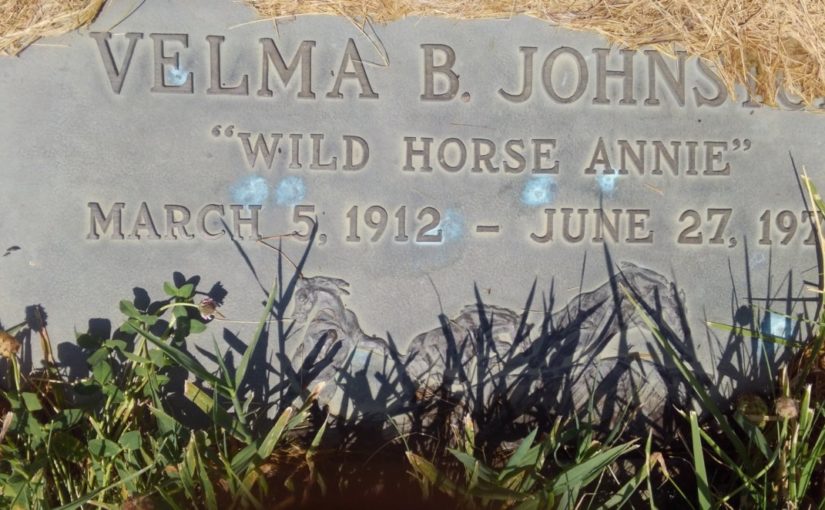

It was a crisp July morning, and I was counting steps in the Mountain View Cemetery in Reno, Nevada. Or rather, I was counting plots. Forty six plots down from the end of the row, and about five plots back from the road. This is what the guy at the office told me, when he…

-

Krause Springs

Krause Springs is not for the weak. It is not for the very young, or the very old. It’s not handicapped accessible, or even that easy for those with balance issues. There are slick spots. There are sharp spots. There are shallow parts and there are deep parts. In order to get to some of…

-

SMTX: Ringtail Ridge Natural Area

There is something exciting about following a path, not knowing where it leads you to. Sometimes, you find something interesting along the way, something that sparks your curiosity and imagination, something that connects you to the past but then also makes you wonder about the future. This is how we felt about the unexpected encounter…